Re-evaluating the role of nucleosomal bivalency in early development

Abstract

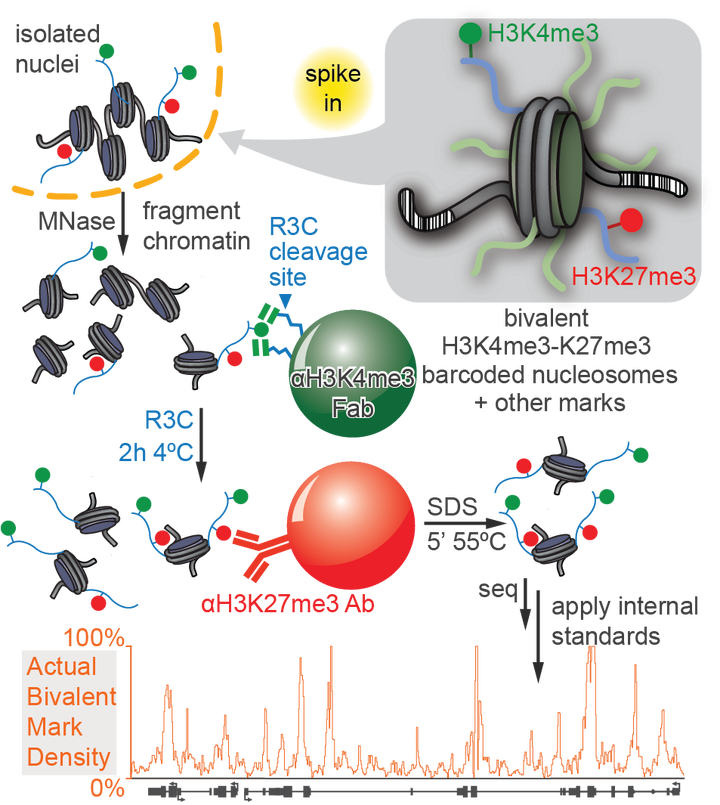

Nucleosomes, composed of DNA and histone proteins, represent the fundamental repeating unit of the eukaryotic genome; posttranslational modifications of these histone proteins influence the activity of the associated genomic regions to regulate cell identity. Traditionally, trimethylation of histone 3-lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is associated with transcriptional initiation, whereas trimethylation of H3K27 (H3K27me3) is considered transcriptionally repressive. The apparent juxtaposition of these opposing marks, termed “bivalent domains”, was proposed to specifically demarcate a small set of transcriptionally-poised lineage-commitment genes that resolve to one constituent modification through differentiation, thereby determining transcriptional status. Since then, many thousands of studies have canonized the bivalency model as a chromatin hallmark of development in many cell types. However, these conclusions are largely based on chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIP) with significant methodological problems hampering their interpretation. Absent direct quantitative measurements, it has been difficult to evaluate the strength of the bivalency model. Here, we present reICeChIP, a calibrated sequential ChIP method to quantitatively measure H3K4me3/H3K27me3 bivalency genome-wide, addressing the limitations of prior measurements. With reICeChIP, we profile bivalency through the differentiation paradigm that first established this model: from naïve mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) into neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs). Our results cast doubt on every aspect of the bivalency model; in this context, we find that bivalency is widespread, does not resolve with differentiation, and is neither sensitive nor specific for identifying poised developmental genes or gene expression status more broadly. Our findings caution against interpreting bivalent domains as specific markers of developmentally poised genes.